Not everyone is as lucky as fiction writers, who can get away with being

That’s writer-speak for “drafting by the seat of your pants” instead of following an outline — and it’s virtually impossible in nonfiction.

Nonfiction demands the use of facts and flesh-and-blood experiences that can’t be dreamed up on the page. There’s no other way to keep your facts straight and build them into a compelling narrative: you have to know how to outline a nonfiction book.

In this article, I’ll show you exactly how to do that.

But first, let’s take a closer look at what type of literature nonfiction even is.

The two types of nonfiction

Nonfiction encompasses all sorts of wildly different books, but it can be classified into two types:

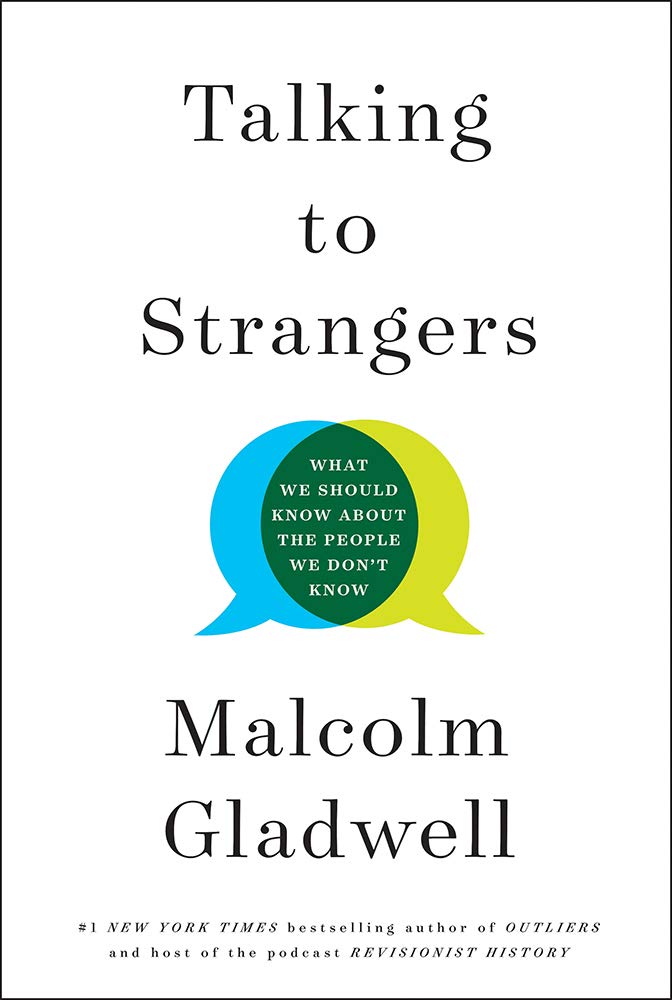

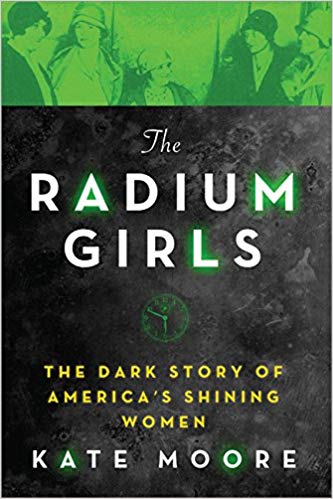

- Literary

nonfiction, also called creative nonfiction and narrative nonfiction - Informative, known also as practical nonfiction

According to prolific author and editor Sol Stein, informative nonfiction “is designed to communicate information in circumstances where the quality of the writing is not considered as important as the content.”

It’s not that the quality of writing isn’t important, but the content is the focus in practical nonfiction.

Books on this side of the spectrum include titles like these below. They often have a self-help, scientific, or historical focus.

Sol Stein also describes literary nonfiction in a helpful way.

He says that literary nonfiction “puts emphasis on the precise and skilled use of words and tone, [and assumes] that the reader is as intelligent as the writer. While information is included, insight about that information, presented with some originality, may predominate.”

Basically, literary nonfiction employs fiction devices like these:

- Sensory details

- Imagery

- Dialogue (which, unlike in informative nonfiction, is not likely to be exactly accurate)

- Experimentation with different tenses, such as the popular present tense

- A novel-like narrative arc

- Fully fleshed-out characters

It’s like doing all the work of a novel but applying it to things that actually happened. There’s room for suspension of disbelief here.

Memoirs often fall into this category.

For example, readers of a tell-all memoir about your abusive mother know you probably didn’t write down every word of every conversation you had with her, but they’ll believe that the gist of your dialogue is true in its own way.

Think Educated by Tara Westover, Reading Lolita in Tehran by Azar Nafisi, and Black is the Body by Emily Bernard.

No matter which type of nonfiction you choose to write, following an outline is important.

Some people hate outlining. Others find it exciting and satisfying and would outline all day if it did all the work of drafting a real book (it almost does, actually!).

No matter what type of writer you are, this guide will help make things easier for you.

The steps you need to take for both informative and literary nonfiction are the same, with small adjustments. So let’s take a look!

5 easy steps to outline your nonfiction book

If you know you want to write a book, you probably have a topic in mind. But even though a book is a long project, keeping the topic narrow and focused is important.

An informative nonfiction book is making a case for something. It’s a 30,000- to

A work of literary nonfiction can span the same page count range. Instead of an argument, though, you must figure out your leading theme.

In both cases, you have to narrow down your topic.

Narrowing down a topic

The first thing you need to do in order to outline your nonfiction book is figure out your argument. What is it you want to prove, teach, or share?

An easy way figure this out? Distill your argument or theme into one sentence before you start outlining a book.

Take the informative nonfiction book Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder by Richard Louv, for example.

The thesis of this book in a single sentence:

Direct exposure to nature [is] essential for a child’s healthy physical and emotional development.

from Last Child in the Woods by Richard Louv

This sentence even appears on the back cover of the book. The author gives everything away from the start, which you wouldn’t do in fiction.

But the argument isn’t a revelation. It’s how the author gets to that point that matters, and that’s what will be inside your outline and later, your finished draft.

Take some time to figure out what this sentence looks like for you. It should be short and to the point, positing an argument that makes readers want to crack open your book to find out how you’ll prove it.

Once you have a couple versions of this sentence written down, test them with potential readers using PickFu. You can choose your target readership, too: if you were Richard Louv, you might select an audience of parents who read nonfiction.

Split-test your two or three sentence choices, asking a simple question:

“Which thesis for a nonfiction book makes you want to read the book?”

You can also select an open-ended poll, where respondents rate your sentence and provide feedback. Frame your question like this, and add an optional star rating:

“Given this thesis for a nonfiction book, how likely are you to want to read the book? Why?”

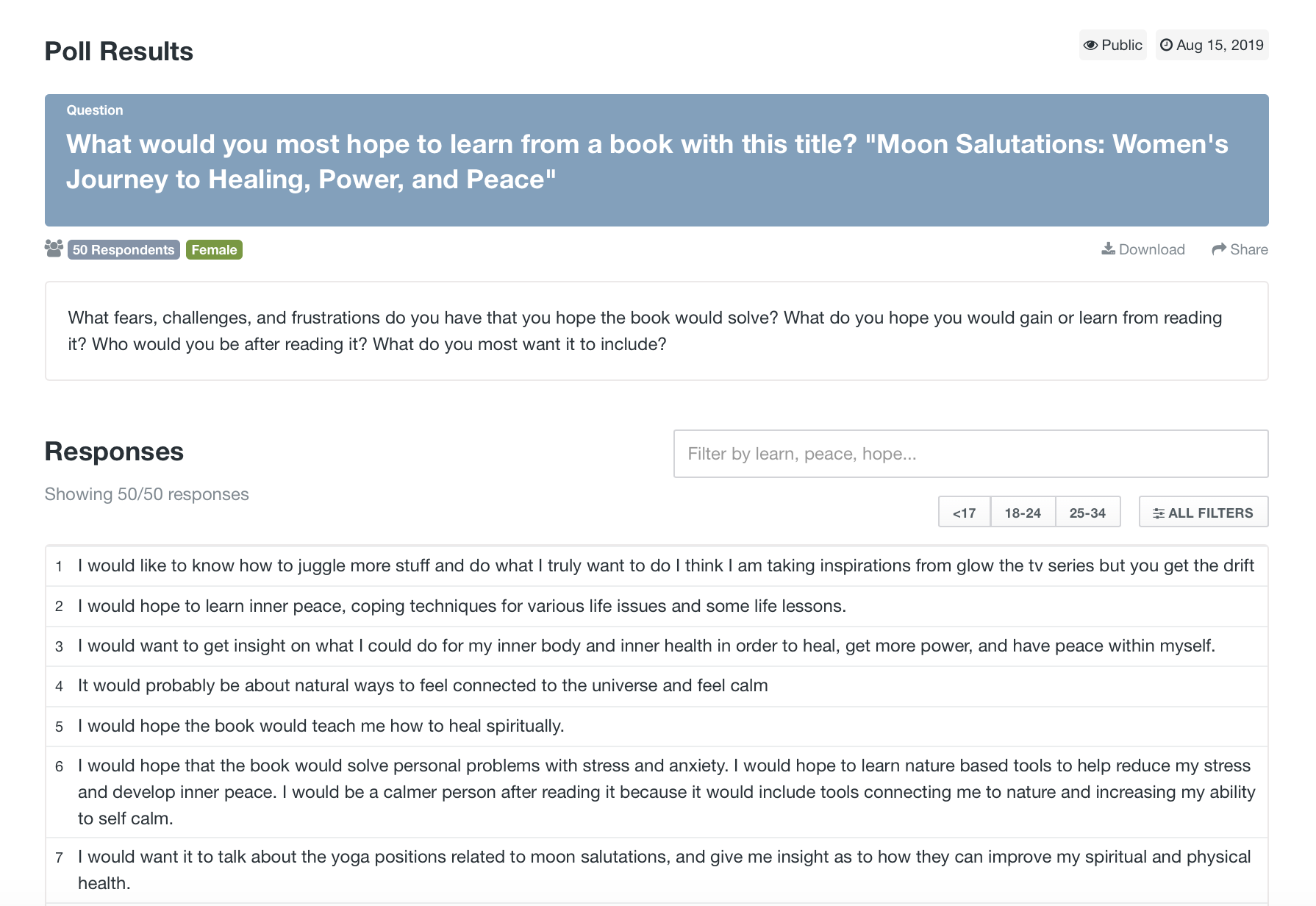

PickFu respondents will provide detailed answers and you’ll be able to read and save each one. You can even turn the topic into a tentative title, like this PickFu user did, and ask specific questions of the audience:

For a literary nonfiction book, you’ll follow the same process — only this time, you’re outlining the theme of your book, not the argument.

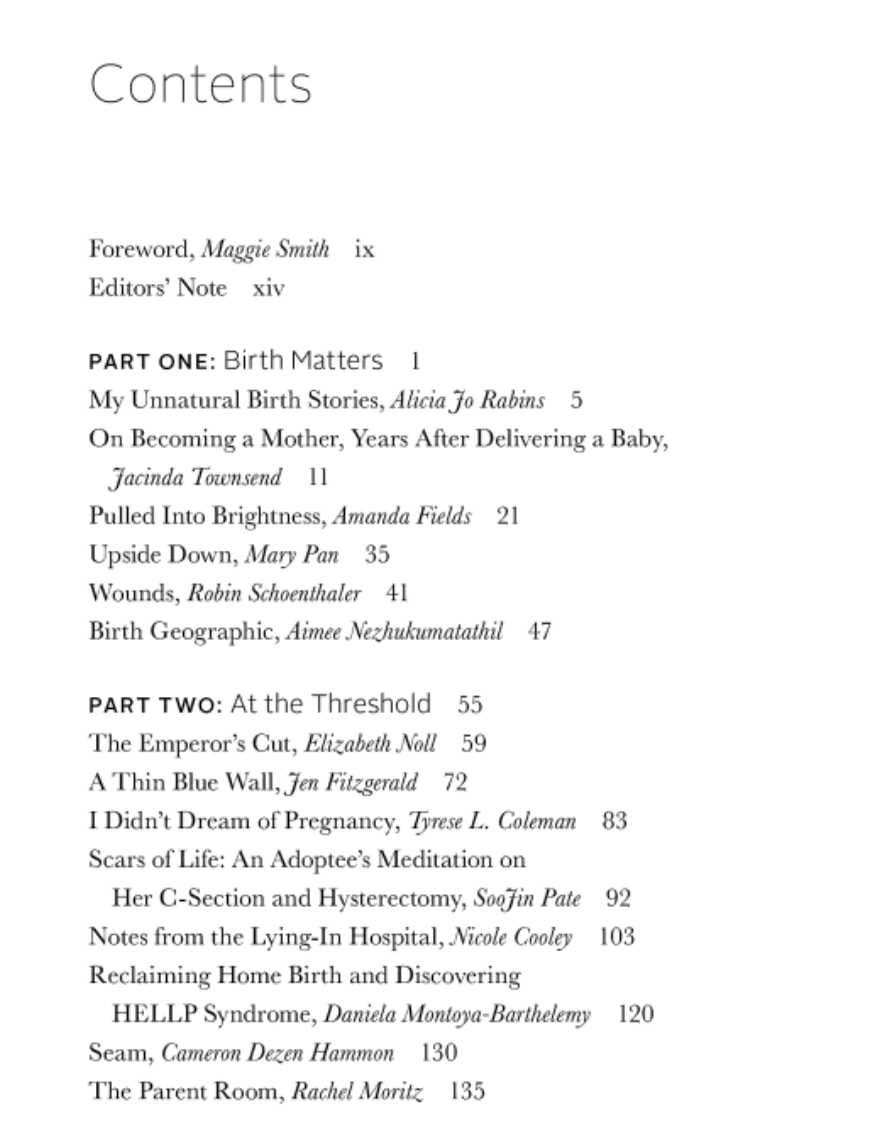

The theme of the landmark book My Caesarean: Twenty-One Mothers on the C-Section Experience and After can be found on its back cover:

A heartfelt meditation…[that adds] back to the [birth] conversation the missing voices of a vast, invisible [C-Section] sisterhood.

from My Caesarean, back cover

The theme here is bringing the guilt, pain, and joy of C-Sections to the forefront of birth conversations.

See how there isn’t an argument? The editors and authors aren’t trying to convince their readership that C-Sections are better than “normal” birth.

Instead, they’re illuminating a wide range of stories that haven’t been listened to or validated.

Keep in mind this key difference when you’re crafting a sentence for literary nonfiction vs. informative nonfiction.

Brainstorming chapter topics

Once you’ve got your overarching topic distilled to one sentence, it’s time to brainstorm chapter topics. This critical step will help you outline your nonfiction book.

For an informative book, your topics will be the supporting arguments that prove your overarching thesis. A literary nonfiction tome, on the other hand, will focus on sub-themes that flesh out your main theme.

Take some time to think deeply about your one-sentence topic.

Then start writing words down on a piece of paper, a stack of sticky notes, a fistful of index cards, or a whiteboard… whatever suits your style.

After this brainstorming session, start organizing your topics into groups. Figure out which topics are the main ones and which are the supporting ones.

Many informative books are divided by parts which are further supported by groups of chapters, like Richard Louv’s Last Child in the Woods:

Think of each part as the main sub-argument to your overarching topic. The chapters inside each part are the main points that support each sub-argument. Don’t worry about organizing the entire table of contents yet, though. Worrying too much about the overall narrative at this point can make you feel stuck. It’s like trying to write a perfect draft the first time around.

In literary nonfiction, the idea is similar except you’re creating sub-themes to support the overarching theme. In each sub-theme, a chapter should spotlight an experience that makes the sub-theme deep, rich, and layered.

Eliminating ideas that don’t work

After organizing everything, you’ll probably have a few topics that just don’t fit anywhere.

Unless you feel they add value and you need to incorporate them somehow, part ways with them. For now, anyway. You never know when you might write another nonfiction book in which to use them.

When you outline a nonfiction book, you might find yourself planning for Book 2 before you even begin drafting. What a gift!

When I’m outlining, I like to keep a notebook or document on my laptop for “scraps,” or parts of my outline that I’ve cut out. This allows me to reclaim those ideas in the future instead of forgetting they ever existed.

You can do the same.

Crafting the overarching narrative

Once you have all your parts and chapters figured out, organize all of it into a compelling overarching narrative.

This is a pretty easy step for a memoir. You’ll probably outline the parts and/or chapters according to the timeline of the events you’re writing about.

It’s a little more complicated with informative nonfiction. A good place to start, though, is with the problem.

Take a look at your PickFu-respondent-approved overall topic sentence. What is the problem your book is trying to prove or solve?

Richard Louv’s Last Child in the Woods tackles the issue of disconnection from nature. In the introduction and first chapter, he talks up his own natural childhood and then argues the new problem for today’s kids: increasing technology and urban development makes it much harder for kids to connect with nature, and this distance costs us all.

The rest of the book works toward the goal of reuniting kids with nature, ending on a hopeful note.

You can do something similar, or if you’re feeling adventurous, try a reverse structure.

Using your outline as a marketing tool

Once your Table of Contents is mapped out, take a version of it to PickFu to get open-ended advice and ratings. Or, create two versions and test them against each other.

This is ideal for writers in a time crunch (which is every writer, am I right?) because you can put your outline in front of 50-500 nonfiction readers and get their reactions quickly. You can even include their format preference (e-book or printed book, audiobook) to your targeting.

In an e-book format, the Table of Contents is included in the book’s preview (Look Inside on Amazon), so it helps you sell the content. Once your reader downloads the book, this TOC is also how they can navigate your book on their Kindle or e-reader.

For these reasons, think of your completed outline of the nonfiction book, aka your Table of Contents, as a powerful marketing tool. It basically presents readers with the argument or themes you’re going to delve into. Make them want to cozy up on the couch with a cup of tea and read the afternoon away.

Outlining your nonfiction book can help you avoid writer’s block. You’ll always know your next step.

And beyond that, it’s a powerful way to get readers interested in your book. Start your outline today, and don’t forget to test it on PickFu once you’re done.

Do you have any tips or tricks for writing tantalizing outlines? Let us know in the comments!